GHOST WARES

︎︎︎

As this is my first journal entry, I’d like to say thank you for making it this far. I’m grateful for your time and I hope you’ll find something interesting within.

I’ve enjoyed photographing people in their environment for as long as I can remember owning a camera. The idea of creating a journal around this, and one’s process within this environment is something I’ve wanted to do for a while now.

I started with a trip to Japan just before COVID-19 took hold, and only recently have I been able to engage with the journal once more. If you have feedback, ideas, or even a simple comment, I’d like to hear your thoughts.

Often I question my own process. I struggle between the certainties and the possibilities. Perhaps this is my attempt at answering these questions.

︎

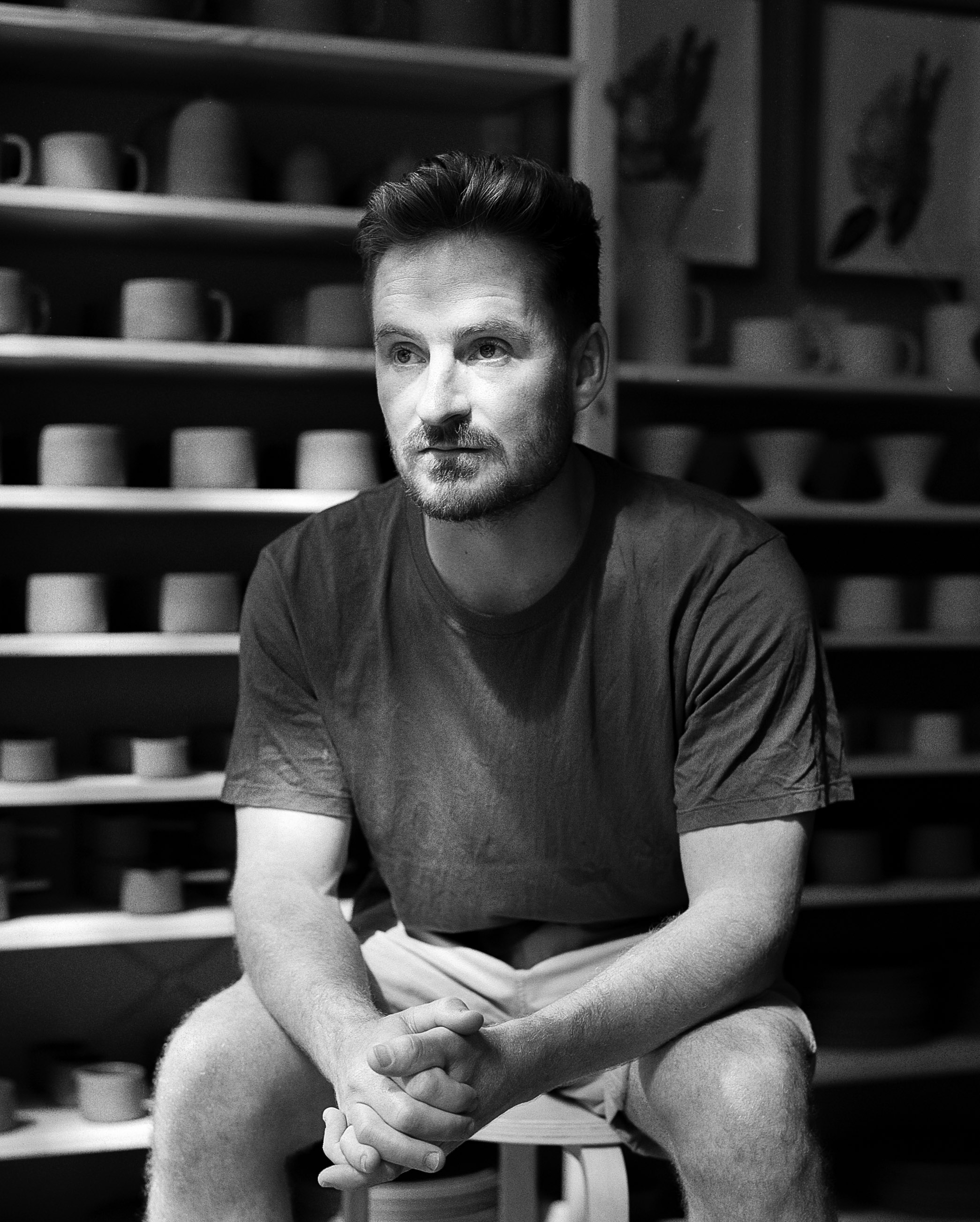

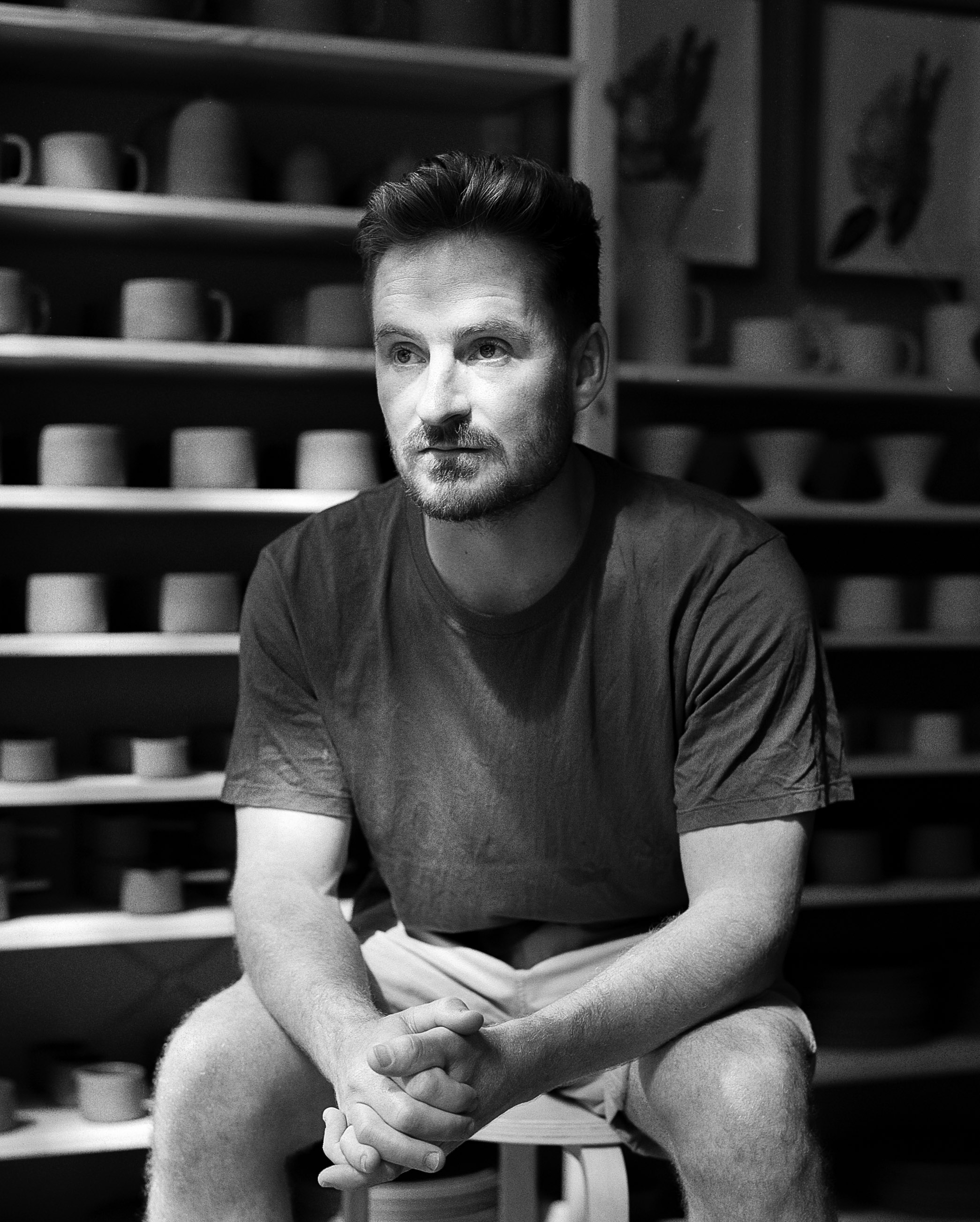

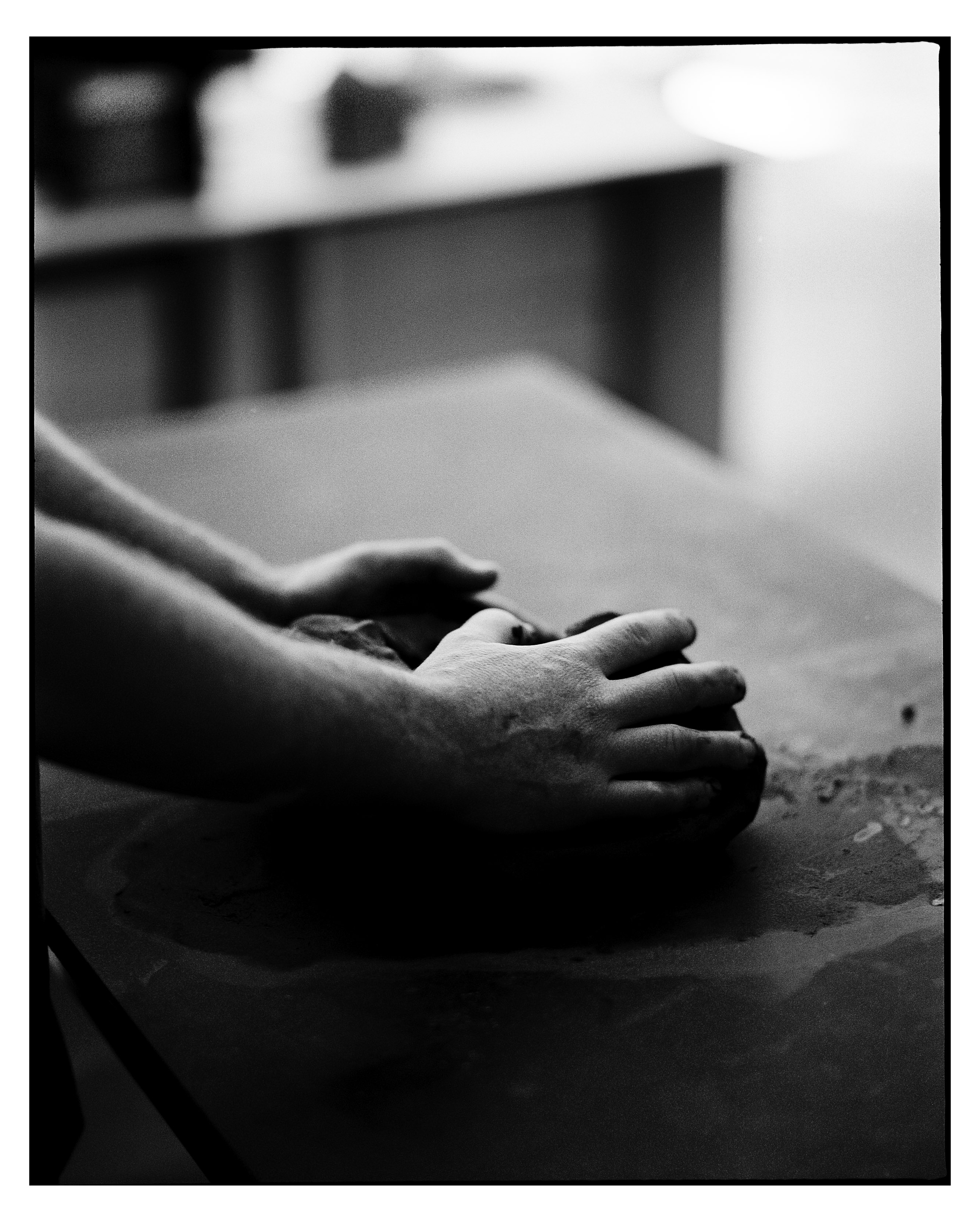

Matthew Vrettas started his ceramics label GHOST WARES in

2016. I first came across his work upon moving to Melbourne in 2018, after a

visit to the Abbotsford Convent where both his current and former studio are

located. For those unfamiliar to the Convent, it was built in the mid 19th

century as a private reformatory for Roman Catholic Girls. It stands a top of

the suburb both beautiful and haunting at the same time.

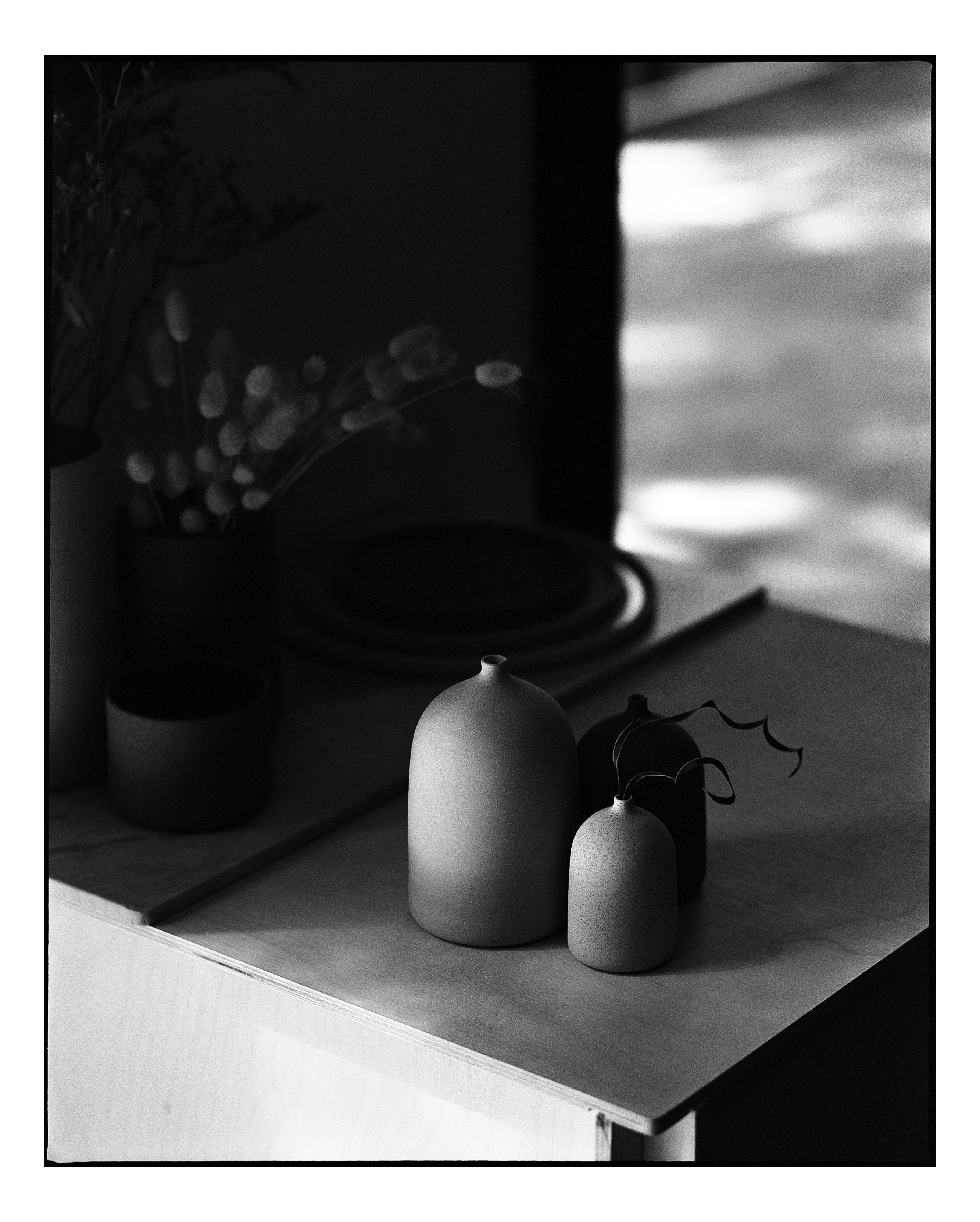

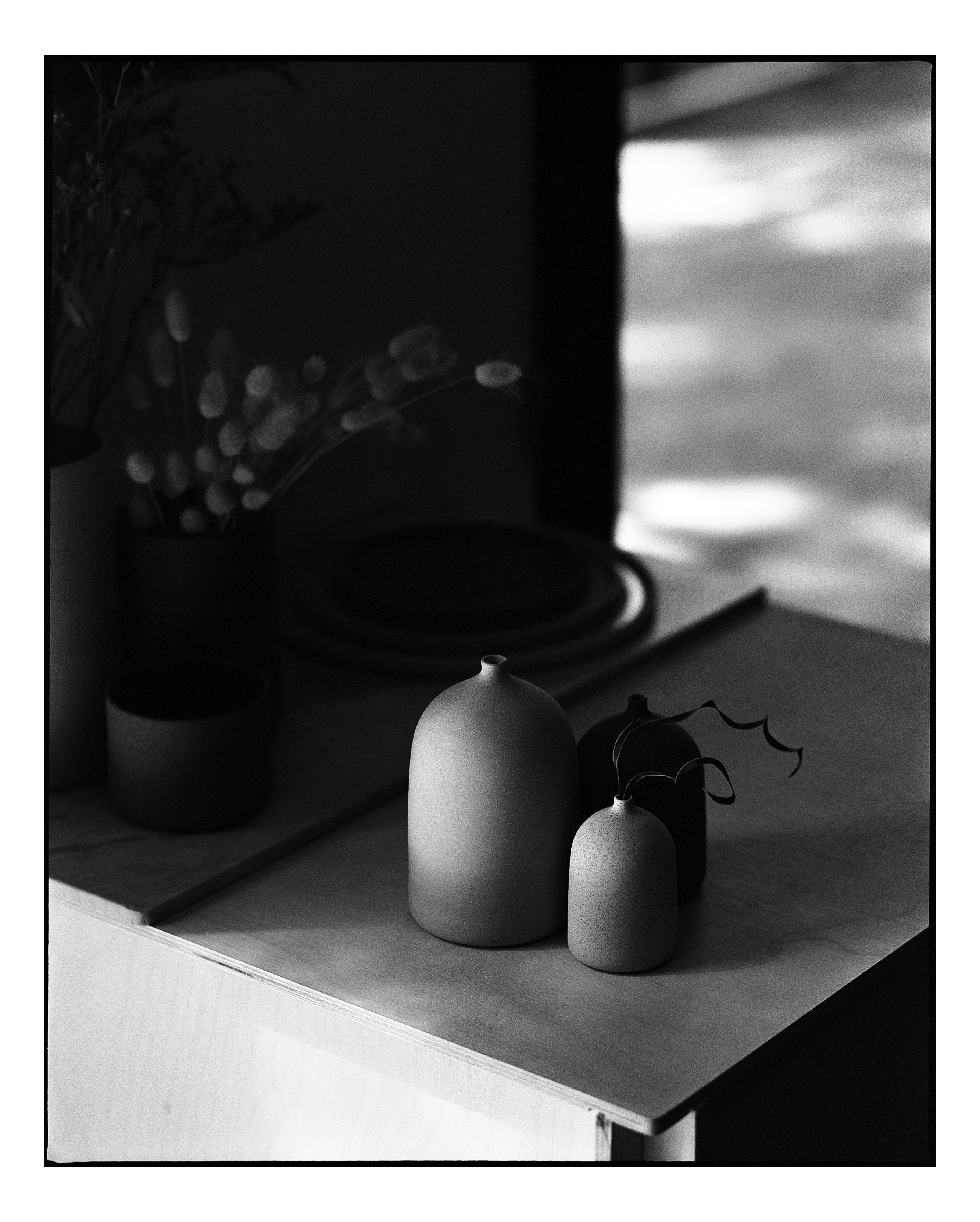

The sandstone buildings differ as you move deeper within, with vignettes closing and opening as you snake your way through. At the time it was his former studio, a small corner junction towards the back of the 16-acre site, which caught my eye. Nice light is often juxtaposed by equally nice shadows, creating the beacon that is contrast. Matthews studio was filled with it. It framed his pieces perfectly.

The sandstone buildings differ as you move deeper within, with vignettes closing and opening as you snake your way through. At the time it was his former studio, a small corner junction towards the back of the 16-acre site, which caught my eye. Nice light is often juxtaposed by equally nice shadows, creating the beacon that is contrast. Matthews studio was filled with it. It framed his pieces perfectly.

His work is finding its way into many homes of Melbourne and abroad. The pieces are handmade and champion the three key elements of good design: Utility, usability and desirability.

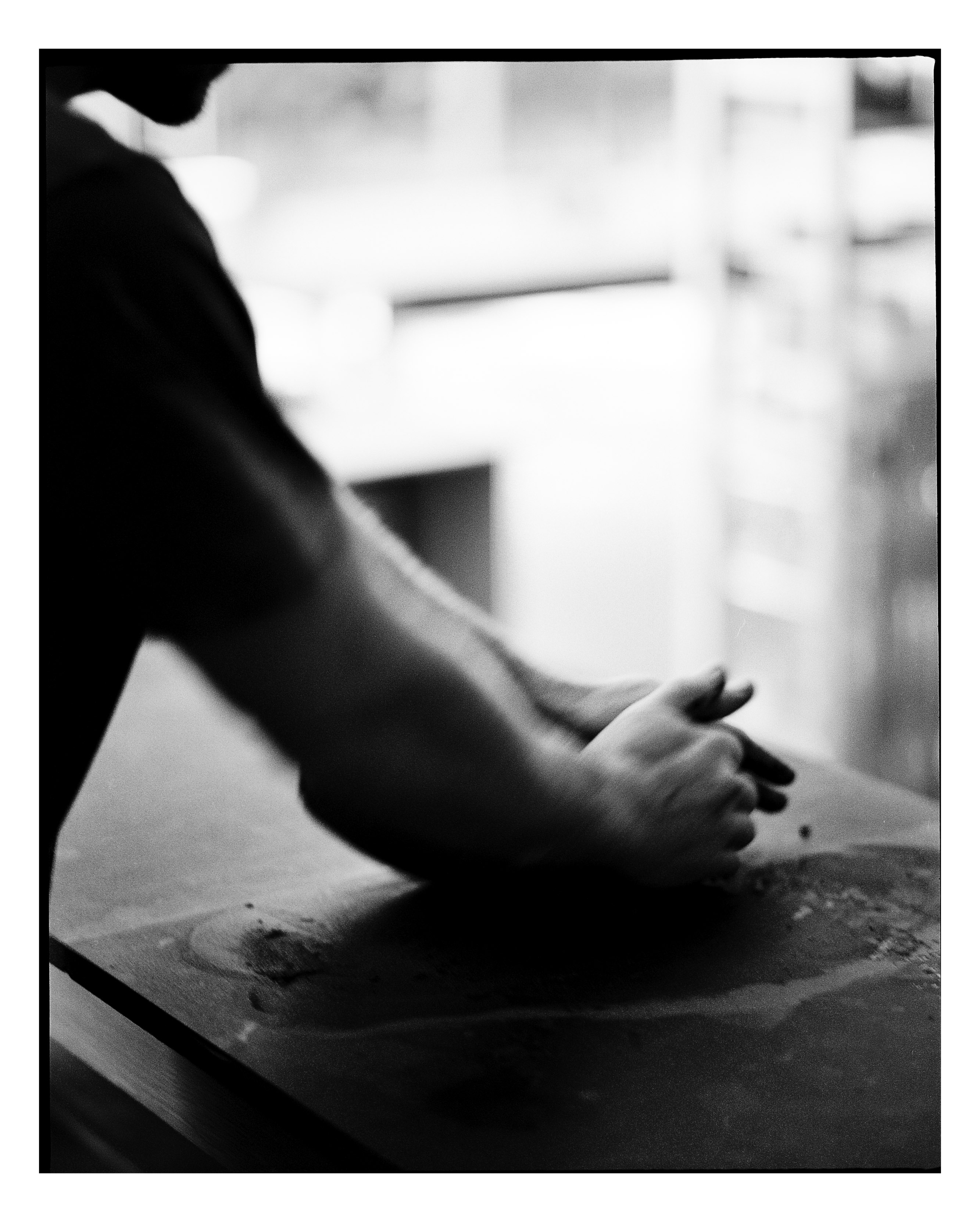

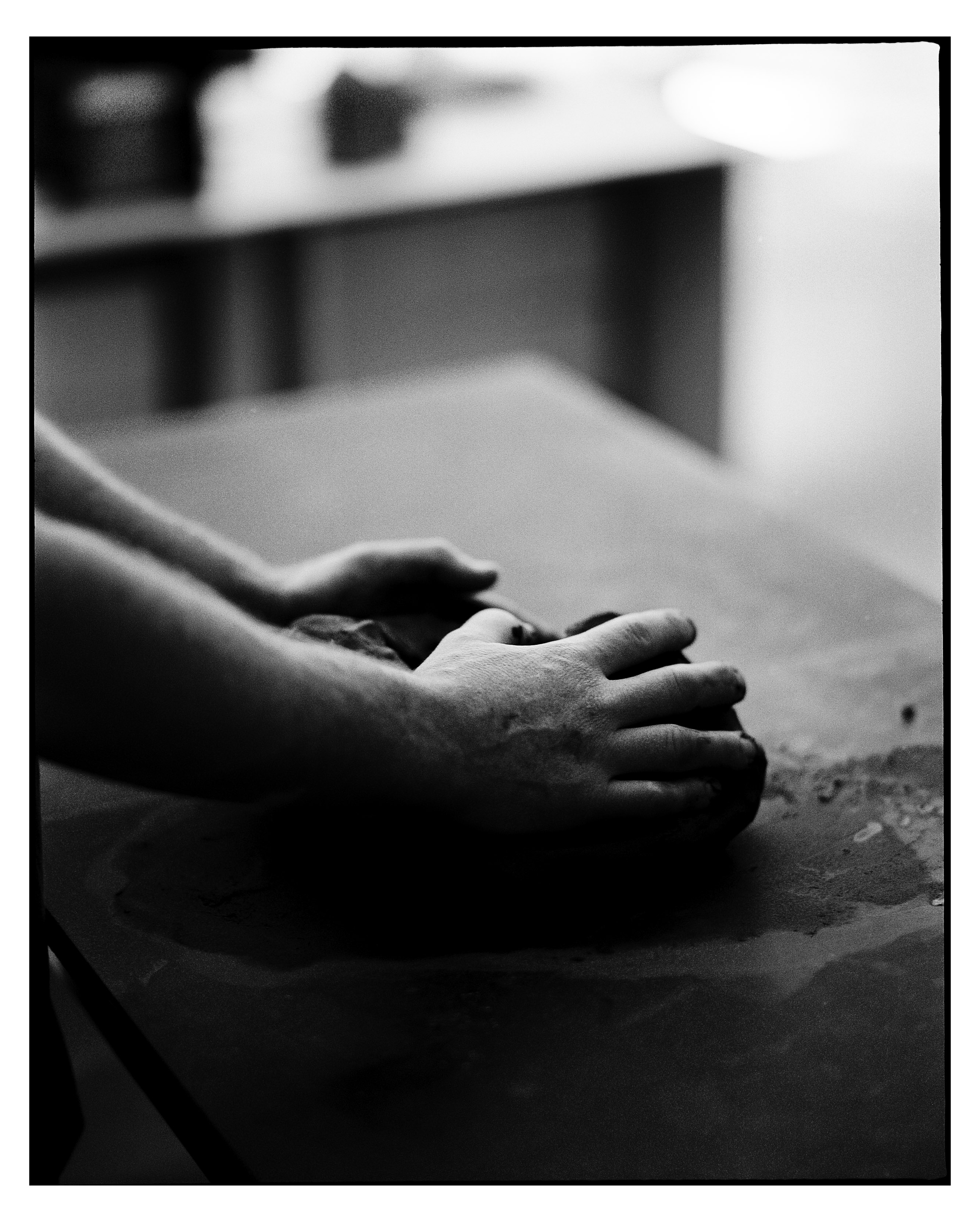

In regards to how his pieces are created, Matthew’s process is methodical and restrained.

“My approach to ceramics has been to focus on the clay itself, by bringing colour and texture in through the clay, I aim to avoid a piece feeling decorated. Each piece is less an expression of me but rather the raw material it is made of.”

The result is consistency and poise. There is an element of

utilitarianism, they have purpose and know exactly what they are. Often, I find

ceramics challenging in their nature, as if i’m not sure what they are or why they

exist. Perhaps this is more a reflection upon myself than the creator’s intent,

however it is the definitive nature of Matthew’s pieces I find calming and

devoid of being contrived.

![]()

![]()

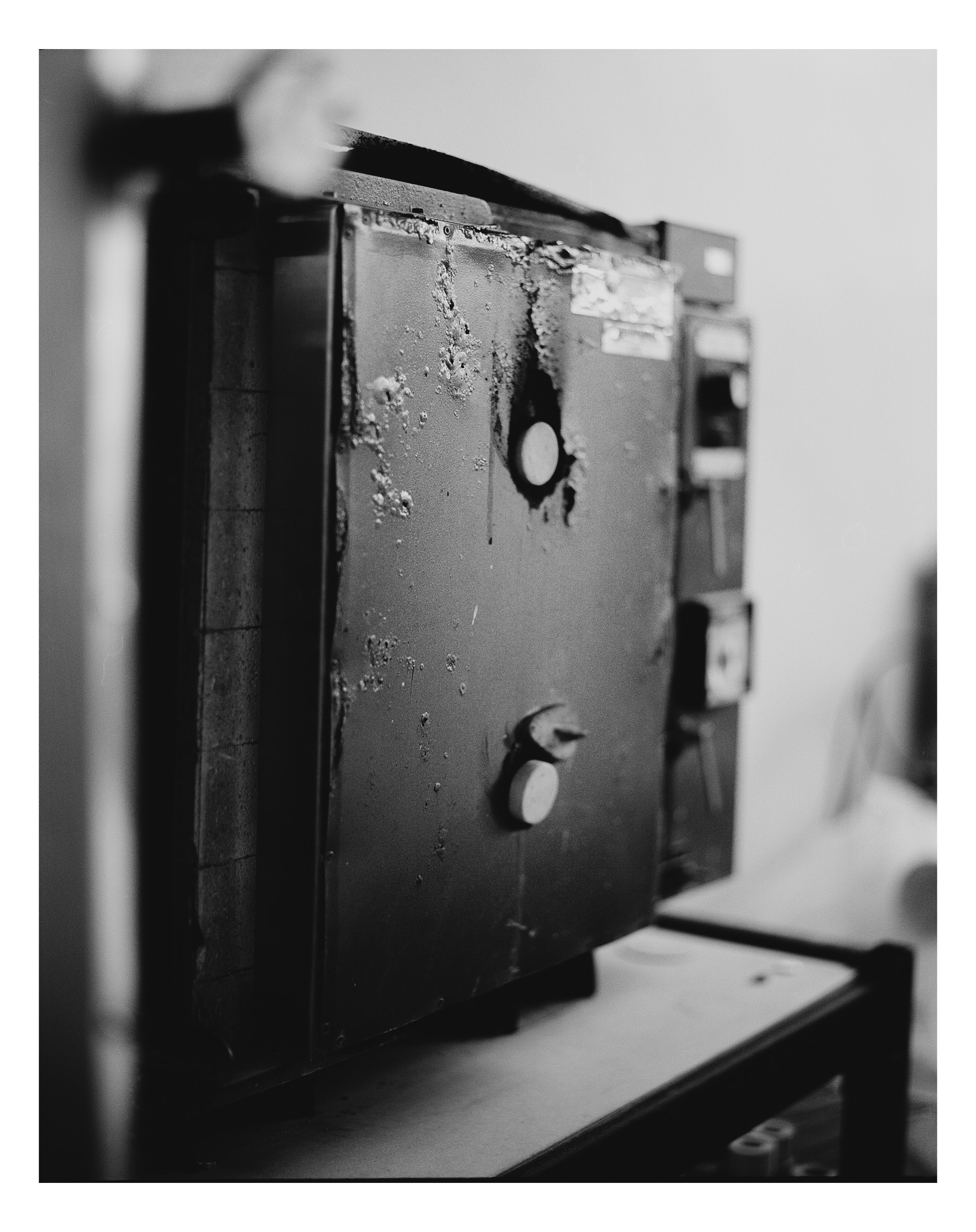

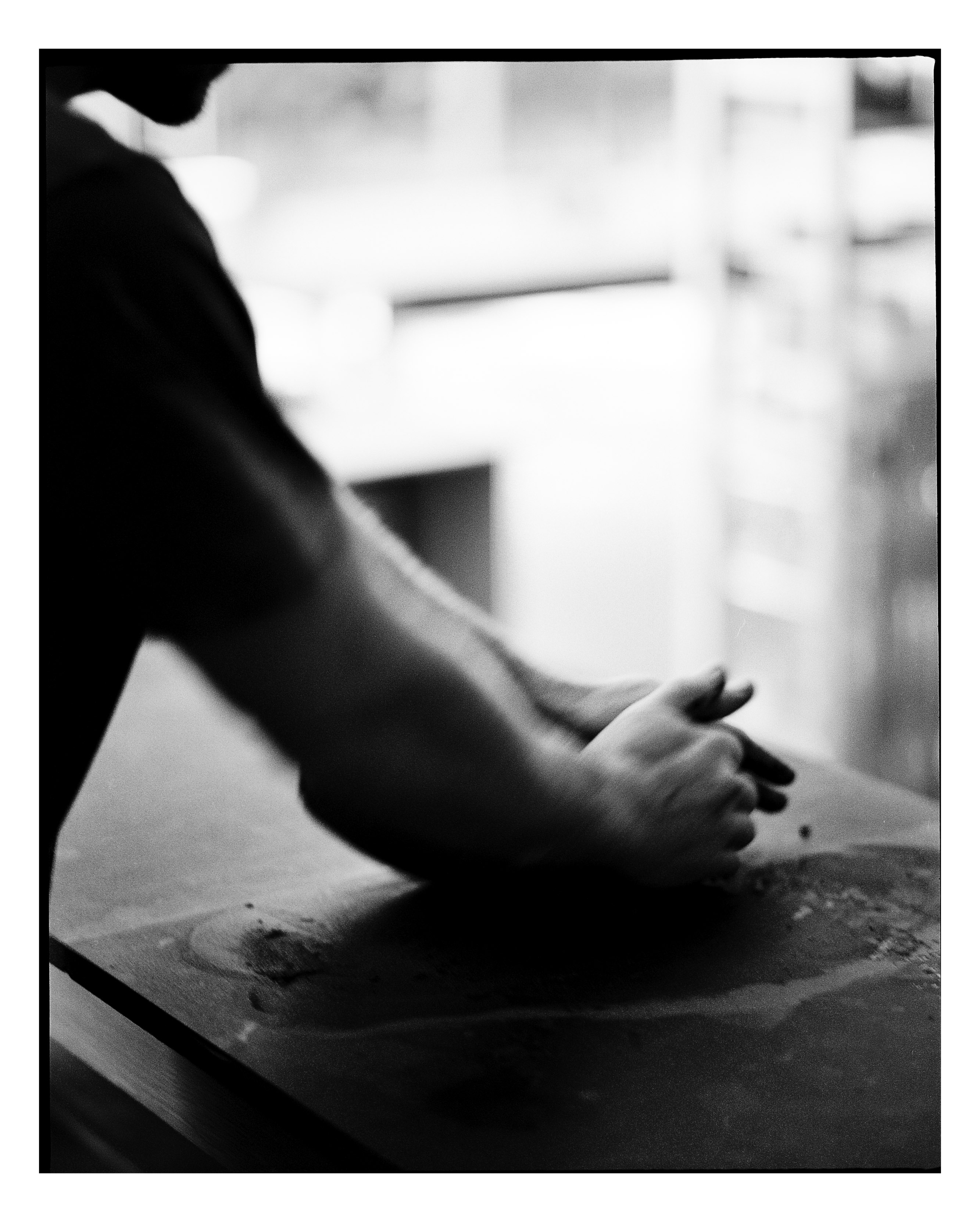

Working in such a linear process doesn’t come without its challenges,

however. The properties of clay remind you of its beginnings within nature, although

offering varying avenues of possibility, it is ultimately something one cannot truly

control.

“I often find it tricky to remain focused on a specific

goal, there are so many possibilities working with clay that I often get

side-tracked by a new idea, leaving the previous project unfinished.

Clay is a

material that particularly lends itself to this, there is so much waiting for

things to dry and go through the kiln, it is easy to become distracted in those

breaks in the process.”

His relationship between process and patience appears to be bound by fate. To give in to process is to have patience and thus dictating the outcome of each piece. Having the humility to understand this is what makes Matthew’s journey in ceramics both taxing and admirable.

“I find the ongoing patience required to be more of a hurdle. The process of working with clay itself requires a lot of waiting, ceramics in general is a patience game, which is a part of the process that I am comfortable accepting. I have an idea of what I would like my studio to be one day and the creative opportunities that could offer, yet the process of building up to that point is a long-term venture and so the patience required for that can be a bit trickier to maintain.”

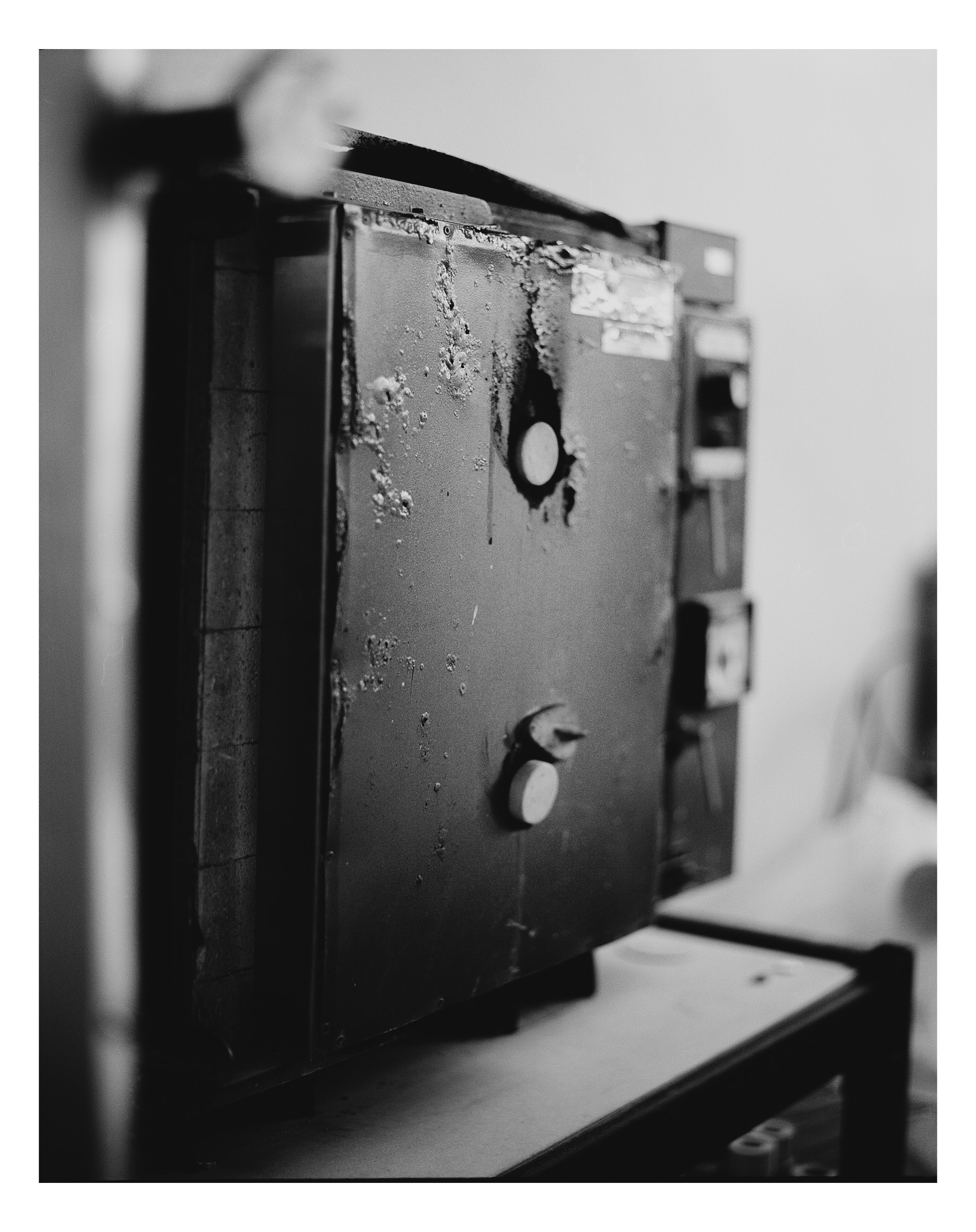

The most interesting element of Matthews process is how his whole craft is dedicated to the creation of something impermanent yet ironically, forged by something intrinsically permanent.

“I like to think of clay as eroded mountains. Time has broken down something that seems permanent, creating a raw material that can be formed into something new. Once a piece has been fired it gains that sense of permanence again, yet with enough time, after I am gone, it could eventually return to its original state, making my intervention just a part of that material's life cycle.”

When asked what the single toughest moment in his journey has been to overcome, Matthew stated such a moment has yet to happen. Rather, keeping yourself focused on the process and having patience to be the larger hurdle.

It was this sentiment that resonated with me the most. Creative industries are habitually lonely spaces to exist in. Very seldomly is the direct input validated. You find yourself questioning what you are doing and why. It becomes cyclical. Only when you succumb to the journey of process, you understand that life itself is such, a combination of states we go through. To paraphrase diarist Anaïs Nin, “Where people fail is they wish to elect a state, and remain in it.”