TOMO KISHIDA

︎︎︎

Often coined the ‘Manchester of The Orient’, the city of Osaka has for several centuries boasted the title of Japan’s merchant city. Although long considered the nation’s primary economic centre, post-Edo Osaka has been happy to play second fiddle to Tokyo in all thing’s metropolis. Where one looks to Tokyo for innovation and novelty, Osaka triumphs on honest middle-class values. It is perhaps with this well documented merchant history as to how Osakans cultivate such a strong community of support toward young individuals looking to go against the norm and start something new. Sakiori Artist Tomo Kishida embodies this notion. “I’ve given up my previous career, my safety net, and my social status. I’ve gone my own way”, he recalls as we watch the wind swirl through his cotton fields. It is within in these fields he stands tall, overlooking the industrial port city where his journey continues.

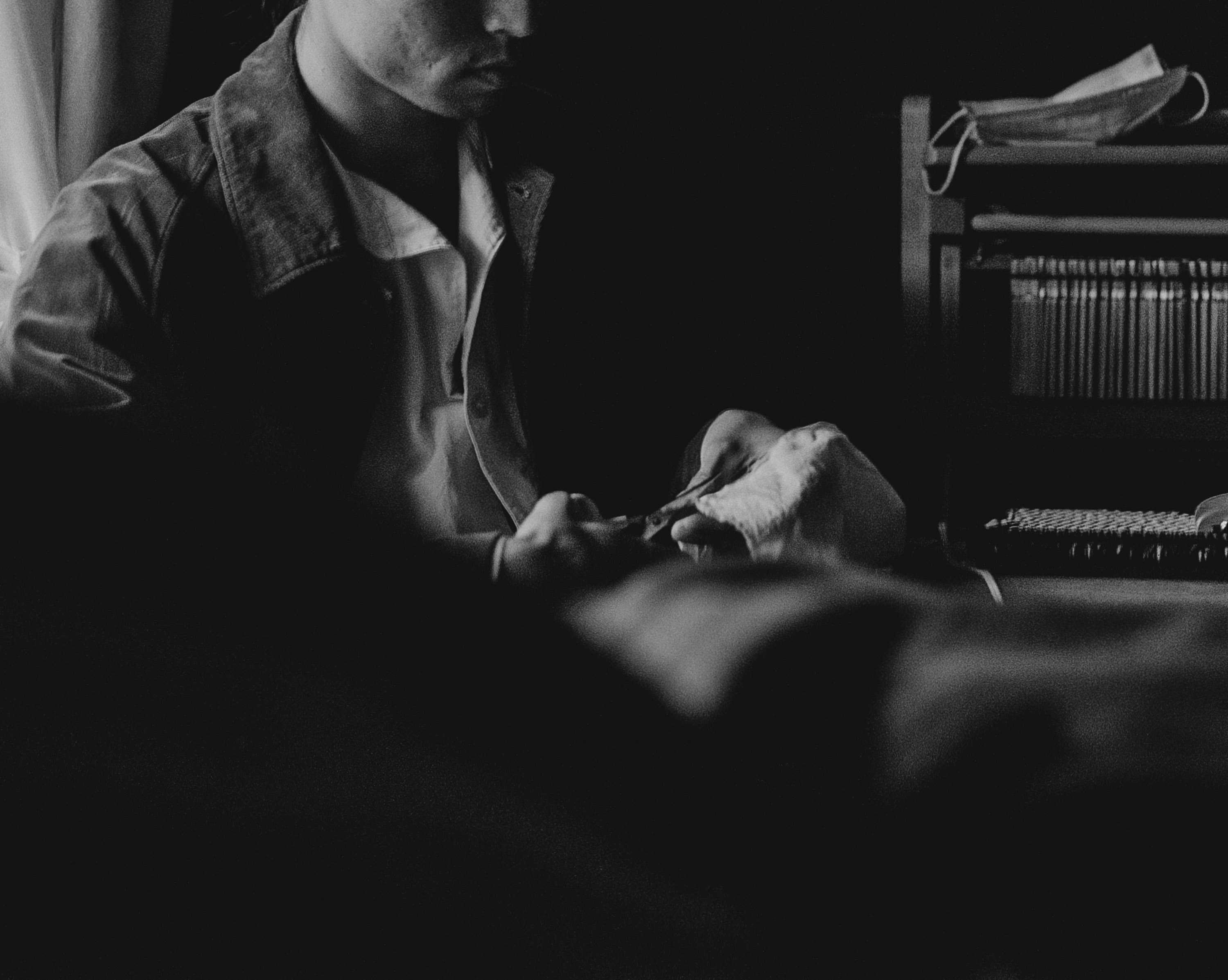

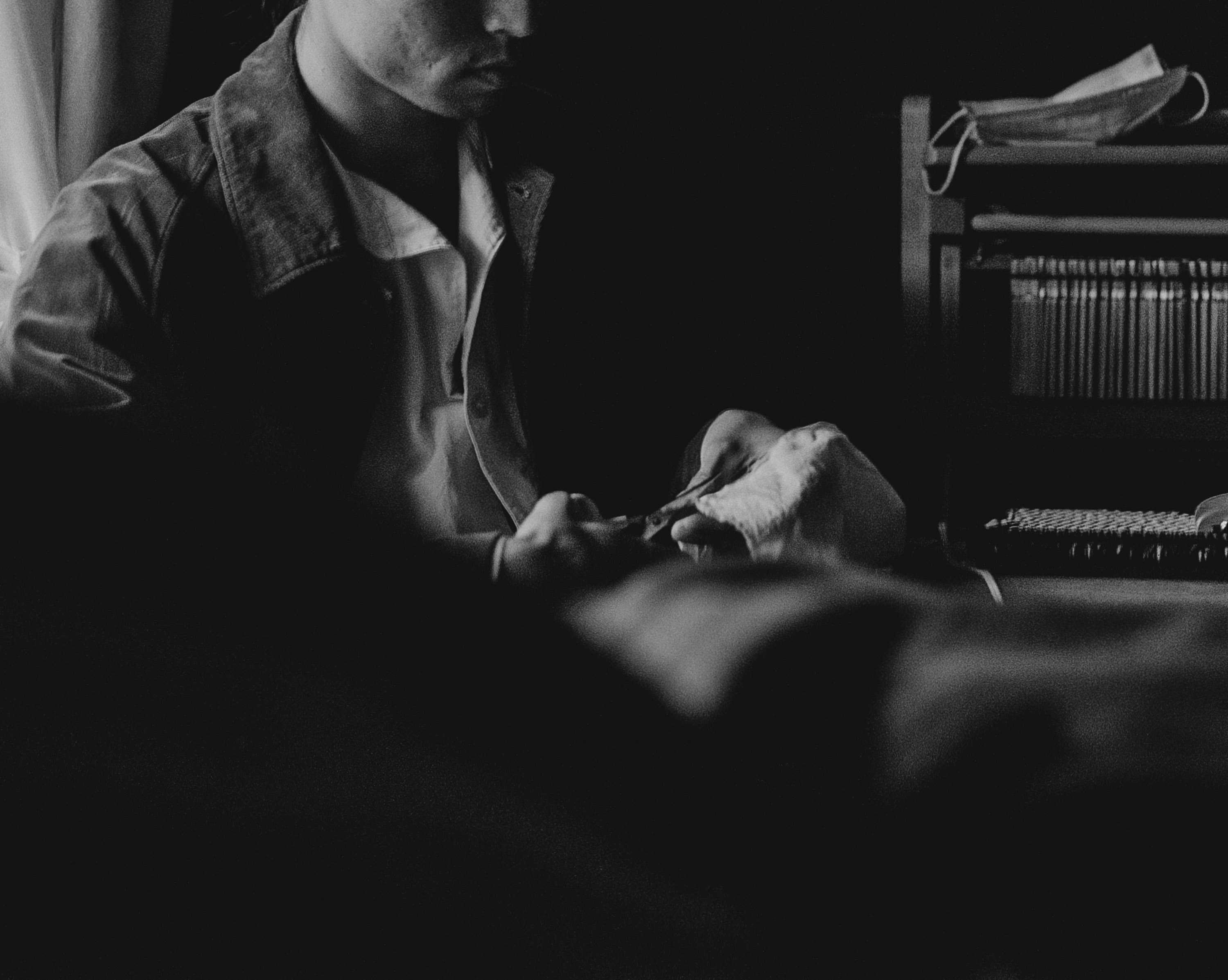

From sowing seeds, spinning cotton yarn, to handloom weaving; for the past four years Tomo has produced one-off pieces of clothing that embody artisanal production. Every piece unique, Tomo uses an ancient Japanese practice known as Sakiori, where pieces of left-over fabric are manipulated and strung back together. Saki meaning ‘to tear’, and Ori to ‘weave together’. The ancient process was created during the colder months in northern Japan where hardy farm women would use a handloom to weave together pieces of scrap fabric to create textiles. The result being a hefty garment fortifying the wearer from the cold. However, Tomo hadn’t always used this process, and it wasn’t until he discovered Sakiori could he reckon his concerns with the clothing industry. “Prior to learning about Sakiori, I questioned whether I was making clothes or simply adding to the problem of mass consumerism. Sakiori changed everything by allowing me to enter a headspace where I can purely focus on craftsmanship”

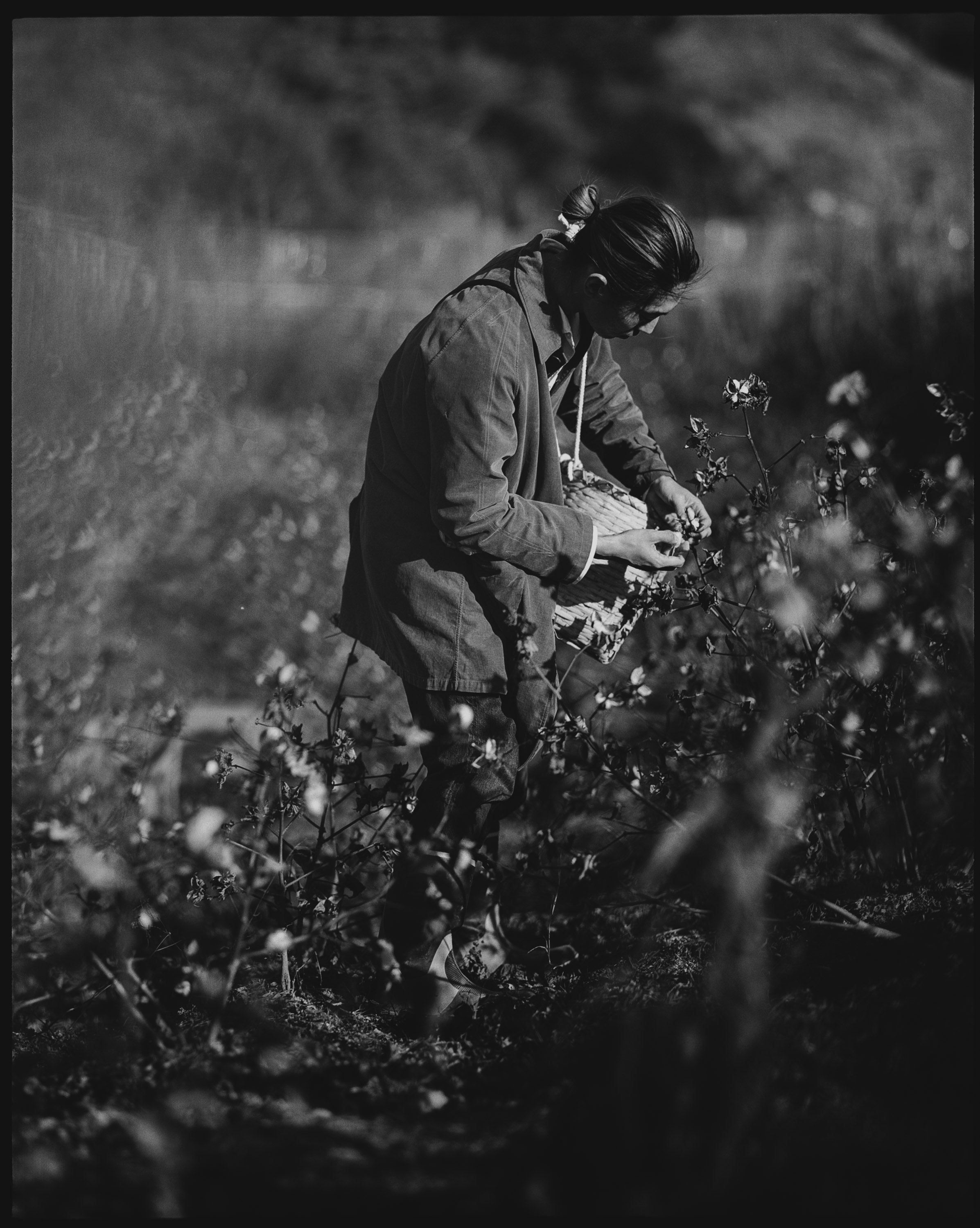

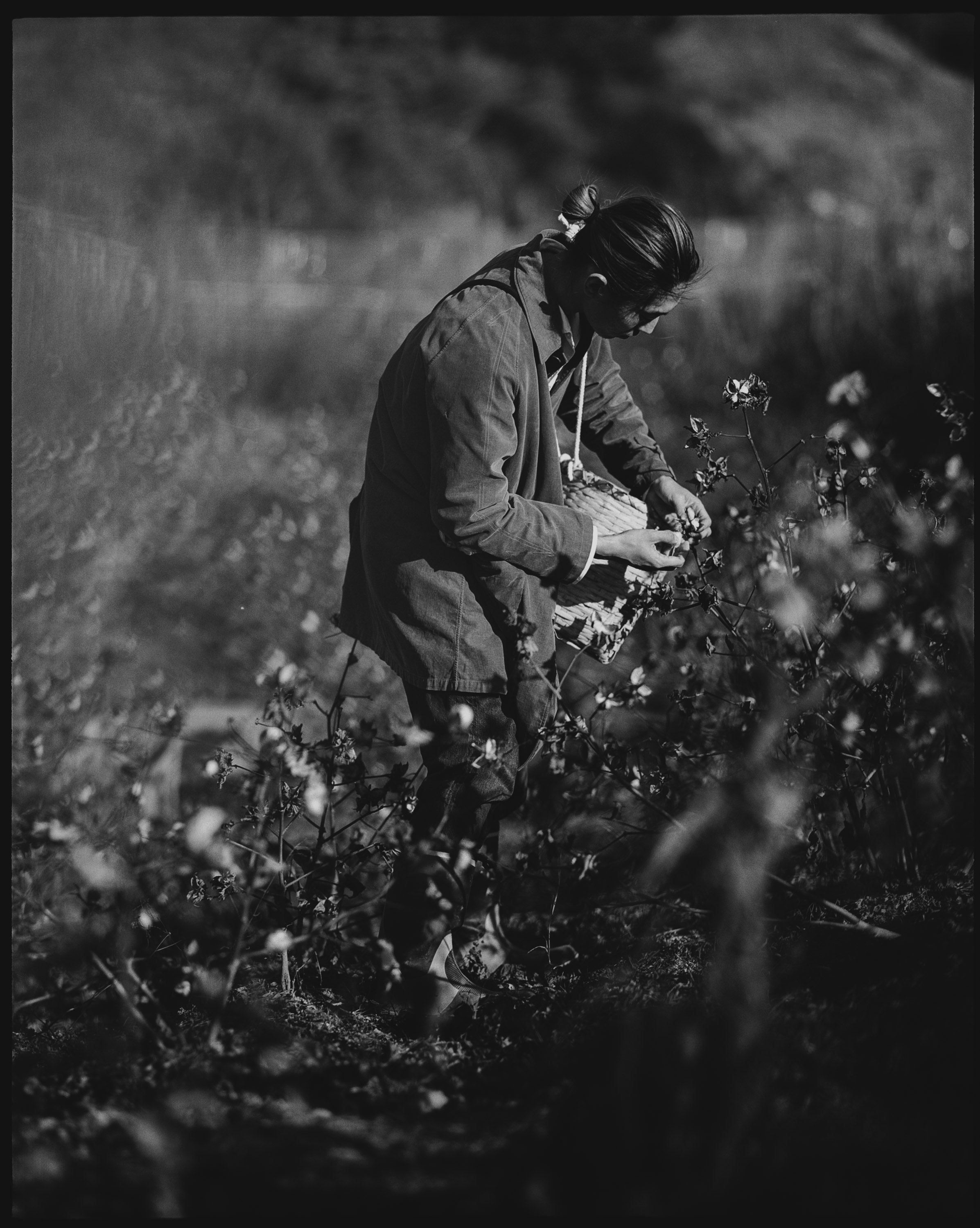

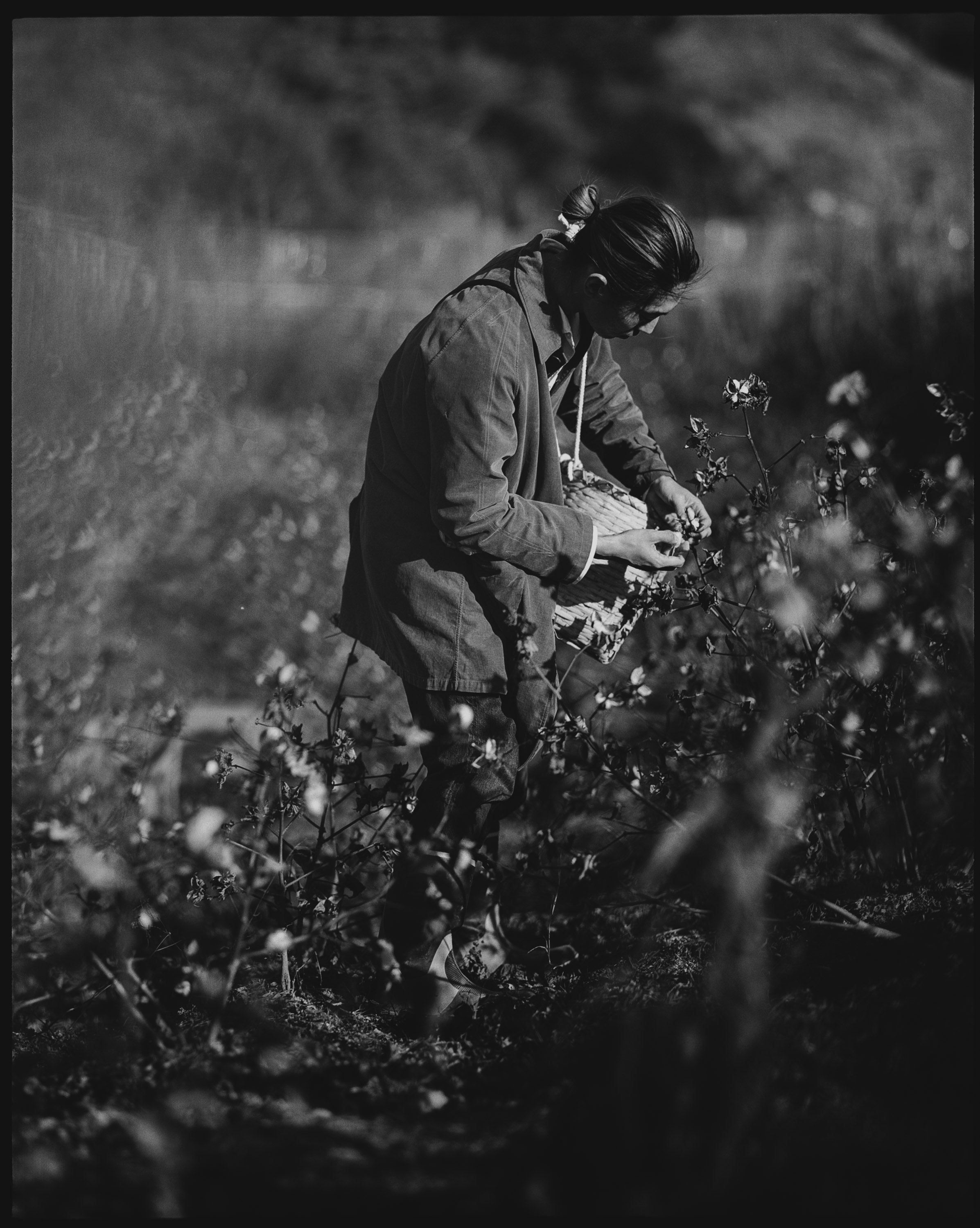

Guiding me through his creative process, Tomo starts in the field. “I want to make pure and primitive things. For me, it all begins in the fields. Every morning I wake up, and I come straight here.” A small plot of land only 10 minutes’ drive up the mountain directly behind his atelier, Tomo began four years ago by planting his first rows of cotton. “My grandfather used this land to grow grapes, not in great quantity, and just for friends and the community. The plot isn’t commercially viable, it simply isn’t large enough.” Small it may be, the possibility of finding such space so close to the city is an anomaly in itself. “Downtown Osaka is only 45 minutes away by train, yet the fresh air rolling in from the bay could make one think they are hours away.”

Only recently has Tomo started to understand the nuances of the plot, allowing him to introduce the cultivation of Indigo. Known as the most widespread and commercially farmed dye plant in the world, Indigo has fallen out of favour with the invention of synthetic dyes. The fact Tomo has chosen to dedicate precious space of his plot to Indigo, shows the holistic nature of his project, in which he coins ‘Land to Skin.’ “I focus on the health of the plants, they let me know when to harvest, I take my small yield into the atelier, I spin the cotton into yarn, and using my handloom I create a textile.”

In determining styles and releases, Tomo looks to his heritage. “Clothes as we know them today are a western custom. Until 150 years ago, all Japanese people wore Kimono. It is important for me to be conscious of this in my design stage. I want people to wear my pieces as an appreciation for the item itself.” This intention clearly highlighting Tomo’s progressive, forward thinking approach to clothing production.

The process being labour intensive, naturally Tomo can only produce a small number of pieces. Yet it is this rarity which makes his label highly sought after, with prices starting around $2000aud per garment. At this price, traditionally Tomo’s label would be considered High Fashion. However, middle class consumer intentions are shifting, with people ‘casting their vote’ with their wallets. In a time where we are consistently reminded of how precious our existence is, seeing ‘Land to Skin’ spread its reach to corners of the globe shows how timely its message truly is.

Often after returning from travel, I find myself revisiting a location through feelings of nostalgia. Usually, the obviously foreign and intriguing experiences are the ones that forge their way to the front, yet it is the attention to detail with Tomo’s project that keeps taking me back. Feeling the cotton between your fingers, to seeing it spun and weaved across fabric, experiencing the full scale of Tomo’s process is an absolute joy. A very tactile experience. “When I think about how my clothes are perceived, I’d like to think there’s a message being delivered. Apart from the apparent concepts of sustainability and design, a large part of what I do operates around this notion of being a pure person and the joy that brings.”

There was no shying away from his humility. Still under 30, Tomo’s mature morals make him seem years beyond his age. “Whatever one does, they should do with pure intentions. I live with pure intentions towards craftsmanship, and it is this pure intention that exceeds understanding and rationality.”

A full circle process, Tomo’s atelier is simply beautiful. Humble, quaint, and slow. A refreshing reminder that one doesn’t need Dad’s backing and a PDF of lofty branding ideas for a turn of career, but rather a sensible approach to working with what you have, and ensuring the process respects that which has preceded.